Food is urban

Food is urban

Explore the intersection between urban food systems and city functions, the interconnected elements that shape how food flows into, through, and out of urban spaces.

Why is food urban?

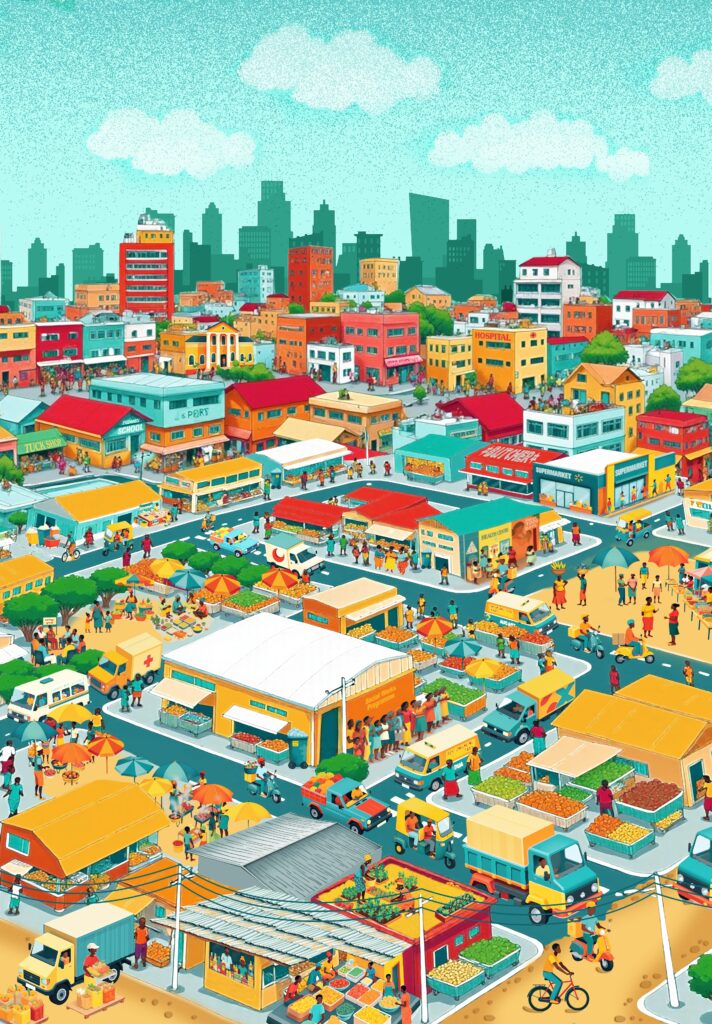

In African cities, food systems are dynamic, shaped by markets, infrastructure, governance, and social structures, which together impact food access, security, and health. Visualising these overlapping systems emphasises how cities influence food availability, choice, and affordability, and how these factors affect residents’ quality of life and opportunities for growth—especially for youth. Each key element, from street vendors and markets to health services and infrastructure, reveals the critical roles cities play in shaping sustainable, equitable, and resilient urban food systems.

Urban food markets

Urban food markets are a primary node of infrastructure on which the urban food system is built across Africa. Urban food markets refer to locally operated establishments within the food economy that offer a variety of food and non-food items, provide employment opportunities, and are characterised by their personalised service, negotiable pricing, and significant cultural and social roles. More than 80% of food consumed in the continent’s growing cities passes through these food markets. Market owners, farmers, vendors, and customers all participate in urban food markets — with an estimated turnover of USD 200 billion to USD 250 billion annually across Africa.

These urban food retail systems tend to be highly informal with small food vendors offering a vital source of food for most urban residents in Africa and providing livelihoods for many, particularly women. However, these bustling hubs often lead to traffic congestion, creating disruptions that prompt discussions on relocating markets. Land value pressures also play a role, as these markets occupy prime urban spaces that can attract redevelopment interests that don’t take nutritional security into account.

Local governments tend to have a clear mandate over market management and the regulation of informal food trade. They also have a mandate of spatial planning and zoning which should dictate how and where supermarkets can expand. Through these two elements they have the power to shape urban food systems.

Food Governance

Current modes of food governance require serious reflection; urban food systems need to be actively governed, not left to chance. Local government mandates enable food governance, particularly in managing the broader food system processes, actors, and services—such as food vending, infrastructure, market support, water and sanitation, support services, and transport. However, the absence of focused governance can have serious and long-term consequences for the sustainability and effectiveness of urban food systems.

In addition to formal governance, informal systems play a crucial role, particularly within food markets. Traders’ associations, for instance, help manage market spaces, resolve conflicts, and assist with waste management—services that local governments may not be able to provide adequately.

National governments also play a role, particularly in regulating food prices and providing subsidies, which directly impact food access and affordability. This should be recognised as part of the broader food governance landscape.

In some cities, traditional leadership can be just as, if not more, influential than local governments, especially when it comes to land allocation for markets. Traditional leaders often serve as custodians of land, shaping the location of markets and influencing food access in ways that local governments may not

Healthcare systems

One of the key outcomes of poor urban food governance is negative health impacts, which affect people across the life course in various ways. These issues contribute to the nutrition transition, a shift from traditional diets to more processed, unhealthy foods, leading to serious health consequences and long-term societal implications. This is experienced differently across various groups within the city, with those living in informal settlements facing the most significant challenges and adverse outcomes. One of the key features of the urban dietary transition is not simply having too little food, but increasingly having too much of the wrong types of food. This leaves cities with the double burden of both hunger and malnutrition as well as obesity.

In many countries, ministries of health are responsible for health and nutrition campaigns, yet they may not have a direct mandate over food systems. This disconnect can hinder coordinated efforts to address food-related health issues effectively. For example, in South Africa, where half of all adults are now overweight or obese, the national health strategy continues to label diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs) as “lifestyle diseases,” implying that poor dietary choices are a matter of individual lifestyle, rather than recognizing them as a poverty issue tied to limited access to affordable, nutritious food.

Children and youth

The growing youthful population in African cities faces significant challenges, including poverty and unemployment, which put pressure on household food quality due to high dependency on fewer working members. While some youth who can afford it may follow dietary trends shaped by advertising that promotes processed and fast foods as fashionable, this can lead to negative health outcomes. However, youth engagement in the food system begins far earlier—particularly in the critical first 1,000 days of life, when inadequate access to nutritious food can have profound impacts on long-term development and future potential. Youth can become powerful agents for change if they are better educated and actively engaged in shaping healthier urban food systems.

Urban agriculture

Urban food growing refers to the production of food, such as crops and small livestock, within urban boundaries. This includes efforts like community and school gardens, backyard and rooftop farming, and other innovative methods to cultivate food in limited spaces. While urban agriculture can supplement rural food sources and sometimes enhance nutrition, its impact varies widely across cities. For example, in cities like Cape Town, Windhoek, Tamale, and Lusaka, urban food production has not significantly contributed to the overall food supply.

Official calls for urban agriculture, while well-intentioned, may inadvertently shift the responsibility of addressing urban food insecurity onto the hungry and poor, rather than prompting decisive action by local governments to protect and support vulnerable populations. Indeed some studies have found urban farmers to be among the most food insecure residents in urban areas. To be effective, urban agriculture efforts need supportive policies that genuinely enhance food access, rather than deflecting responsibility.

Cash transfers

Social grants, offered by governments and charitable non-governmental organisations, are essential in helping vulnerable groups access food. Food vouchers, cash grants, and funding for community kitchens improve food security by providing direct support to those in need.

Social welfare grants can take many forms and target different groups in society. Common examples include pension grants for elderly residents, child grants for parents of young children, and emergency cash transfers to families following specific disasters or shocks.

Built infrastructure

Urban infrastructure—transport, energy, water, sanitation, and waste management—shapes how, where, and what food is accessed and consumed. Reliable transport systems are crucial for timely food distribution; poor systems lead to delays and increased food loss. Energy access, including electricity for refrigeration and cooking facilities, influences household food choices, while clean water and sanitation are essential for food safety in markets, homes, and institutions. Effective waste management keeps markets clean, reducing pests and protecting food quality.

Local governments typically hold the mandate to deliver infrastructure, while food systems often fall under county, provincial, or national jurisdiction. Highlighting the connection between food and infrastructure can help elevate, and justify, the role of local governments in supporting food systems.

Emerging research confirms that infrastructure access is a major driver of food security in African cities.

School nutrition

Social services, such as school meal programmes, play a critical role in supporting children from low-income households. By providing nutritious meals at school, these programmes not only improve children’s nutrition but also encourage school attendance, helping to prevent dropout among those who might otherwise leave school due to food insecurity.

Currently school meal delivery is relatively low in most African cities, but a growing focus on the importance of providing meals to children in creches and schools is starting to change this. Because of the high costs associated with these programmes, efforts to expand the coverage of school meals across the continent requires close collaboration between local and national governments as well as parents, donors and private sector actors.

Street vendors

Street vendors set up along major transport routes, roads, and within informal settlements, offering convenience and accessibility. They are often preferred by low-income residents for their personal relationships with traders, offering food in smaller units, and sometimes credit options. By bringing food directly to residential areas and transport hubs, these vendors reduce the need for costly commutes to larger markets. |

Direct food aid

Social safety nets play a crucial role in helping individuals and families manage risks and navigate economic volatility, offering protection from poverty and inequality while creating opportunities. These programmes provide targeted support to vulnerable groups, including the elderly, persons with disabilities, orphaned children, and other disadvantaged populations, ensuring their access to essential goods and services and preventing destitution.

Examples of social safety nets include food parcels, emergency food relief from organisations like the Red Cross or the World Food Programme, and other forms of aid delivery to communities in need. This highlights the distinction between social safety nets and grants, cash transfers, and other social services.

While emergency food aid programmes are often run by large international organisations, local residents and NGO’s also play a prominent role in providing local food aid to vulnerable communities. The local efforts are often volunteer run and offer very cost-effective support due to their simple and decentralised natures.

Supermarkets

Supermarkets are expanding across many African cities, providing a significant source of food—primarily processed, imported items, with some also offering fresh produce. While they can crowd out smaller, informal businesses, it’s common to see informal vendors operating nearby or just outside. Supermarkets are emerging in some regions but remain inaccessible to much of the urban population, not necessarily serving the majority.

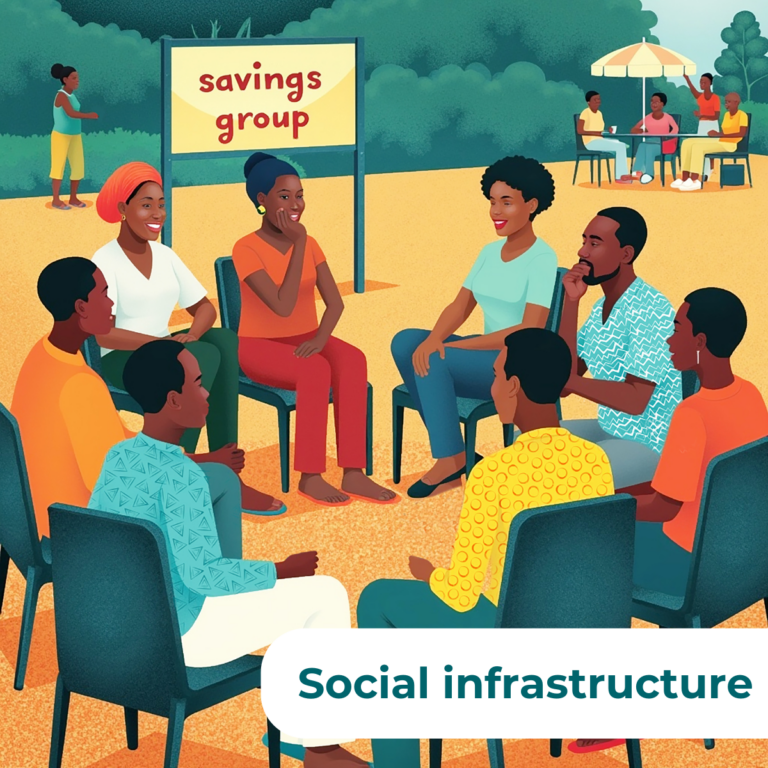

Social infrastructure plays a crucial role in supporting members of inequitable urban societies. These structures, such as group savings and loans, enable small-scale food system actors to access essential capital, and allow members to pool resources to purchase food—typically non-perishables—in bulk for their households. Despite being vital to the functioning of urban food systems, these informal systems are often overlooked, undervalued, and left out of formal policy considerations.

Logistics systems

Metropolitan wholesale markets act as central hubs for food distribution, receiving goods from surrounding regions and supplying both formal and informal markets throughout the city.

Social infrastructure